Did the World’s Largest Flower Once Grow in Hong Kong?

Plants are great travellers and have colonised, flourished but also perished in many places. Patterns in plant distribution have emerged over many millions of years of evolution. The southeast Asia biodiversity hotspot, including the South China floral kingdom, is today one of the most diverse in the world, and some flowers such as the Rafflesias only occur there. The peculiar plant family Rafflesiaceae contains around 36 known species, all of them parasitic, including Rafflesia arnoldii, the world’s largest flower. Is it possible that these strange but captivating plants could once have been found in Hong Kong’s primeval forests?

Sapria himalayana female and male flowers growing in Xishuangbanna, southwest China |

|

Floristic and biogeography research

To understand the composition and ecology of the vegetation of an area, scientists conduct floristic and biogeographic research. Floristics is the identification and study of all plants in a particular area, whereas biogeography is the study of distribution patterns particular to certain groups of plants.

Many botanists are particularly interested in how plants have moved around the world over the course of geologic time. But you might ask: do plants move? Yes – a lot more than we actually think! Though they have no legs, they can travel in the form of seeds, spores or small portions of stems and roots. In fact, in the distant past, many plants crossed continents when they were still connected in one huge landmass. Besides, some seeds can even float across oceans and colonise islands, whereas others have special adaptations, such as winged fruits, that allow them to be dispersed by wind.

From where do Hong Kong’s native plants originate?

Because of the long anthropogenic history of modification of Hong Kong’s natural vegetation – with archaeological evidence for deforestation going back more than 6,000 years – it is extremely difficult to trace back the formation of our native flora.

Sinopora (Lauraceae) is the only plant genus that is thought to be genuinely endemic to Hong Kong today. It contains just one species, S. hongkongensis, which has only ever been recorded in the New Territories – and nowhere else on the planet. However, the vast majority of Hong Kong’s native plants are considerably more widespread and are in fact part of the South China floral biome – an area stretching from western Yunnan to southern Taiwan, including Hong Kong as well as Hainan island. In total, 12,844 species and 227 families of plants have been recorded in this area, and more than 80% of them are also found in parts of India, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Vietnam, a larger “bioregion” known as the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot. These species account for 42% of all the plant species known in China as a whole, despite being restricted to a comparatively tiny fraction of its entire land area.

Southeast Asia bioregions including the fault lines along which land masses and their associated flora may have moved. Note that Hong Kong is located at the extreme northeast of the seasonal evergreen forests of South China, northern Myanmar and northeast India, northern and southern Thailand, northern Laos and Vietnam.

Even within the South China floral biome, there is a distinction between species occurring towards the western part and those found towards the eastern part. The imaginary line separating these two parts, known as the Hua line after the scientist who first defined it, essentially divides the flora of southern Yunnan from that of eastern Yunnan and Guangxi, Guangdong. This separation may have arisen due to plate tectonics, past climate change, or both. Whatever the precise reason or reasons, several plant families are today only found to the west of the Hua line and are accordingly characteristic of the modern flora of tropical Southeast Asia; only in a limited number of cases do their members stray to the east. Classic examples include the Dipterocarpaceae, whose towering hardwood trees dominate the rainforests of Malaysia and Indonesia, and Rafflesiaceae, whose massive flowers bewilder visitors to these forests.

However, this separation is not clear cut and many families have successfully migrated across the line and spread out and speciated at a later stage. For example, several Dipterocarpaceae fossils have been found as far east as Fujian province, though not -- so far -- Taiwan. This suggests that, in eons gone by, the southeastern seaboard of China did indeed support moist tropical forest.

Given all this, there is no straightforward answer in unpicking the complex back-story to Hong Kong’s original vegetation. But, overall, we can deduce that the flora of Hong Kong has more in common with that of Guangdong and nearby parts of southeastern China, as well as neighbouring northern Vietnam, as opposed to in the flora of Western China, Thailand, Myanmar, India and the Philippines.

Rafflesiaceae – a peculiar plant family endemic to Southeast Asia

This brings us back to Rafflesiaceae, a bizarre family of parasitic plants unique to the moist tropical forests of Southeast Asia. All members of this family inhabit the woody stems and roots of a certain kind of vine in the genus Tetrastigma (Vitaceae) – a characteristic formally called endo-holoparasitic -- and their presence only becomes apparent when they bloom – sending forth the most amazing flowers, among them the world’s largest, with a diameter of almost one metre! These flowers not only look strange but also emit a putrid smell that attracts flies as pollinators. The closest known member of the family to Hong Kong is Sapria himalayana, which occurs in Yunnan province in China, as well as parts of India, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

|

|

Numerous attempts to propagate Rafflesiaceae plants for cultivation have been made, both for conservation and tourism. However, so far these have not been successful. In fact, very little is known about the ecology of Sapria. This is partly due to a lack of understanding of its complete life cycle, seed dispersal and germination, as well as insufficient knowledge of the broader concept of the cultivation of endo-holoparasitic plants.

|

Rafflesiaceae’s host, D Tetrastigma laoticum, has a flattened, flexuous stem |

Our research is aimed at answering several questions that could explain the current distribution of Rafflesiaceae. As an endo-holoparasitic species, the complete life cycle of Sapria himalayana is hidden out of sight and it only reveals itself when the incredible flowers emerge from the host. Identification of Tetrastigma host species and their distribution is still a challenge, because the taxa are morphologically similar. Using next-generation sequencing data could help solve this problem and may potentially confirm the host distribution, including its occurrence in Hong Kong. Another key question in Rafflesiaceae biology study is seed germination. Indeed each fruit produces thousands of tiny seeds, however the seeds can only germinate next to their host. The undeveloped embryo development within each seed, the signalling molecules exudated by the host and how the protocorm – the primitive undeveloped embryo -- can penetrate and grow within Tetrastigma hosts are some of the holy grails of research in Southeast Asian flora. Finally, the study of Rafflesiaceae phylogenomics and population genomics will allow us to understand past distribution and the general trend of expansion and reduction of its natural range.

Fruit of a Rafflesiaceae |

An experimental set up to see. |

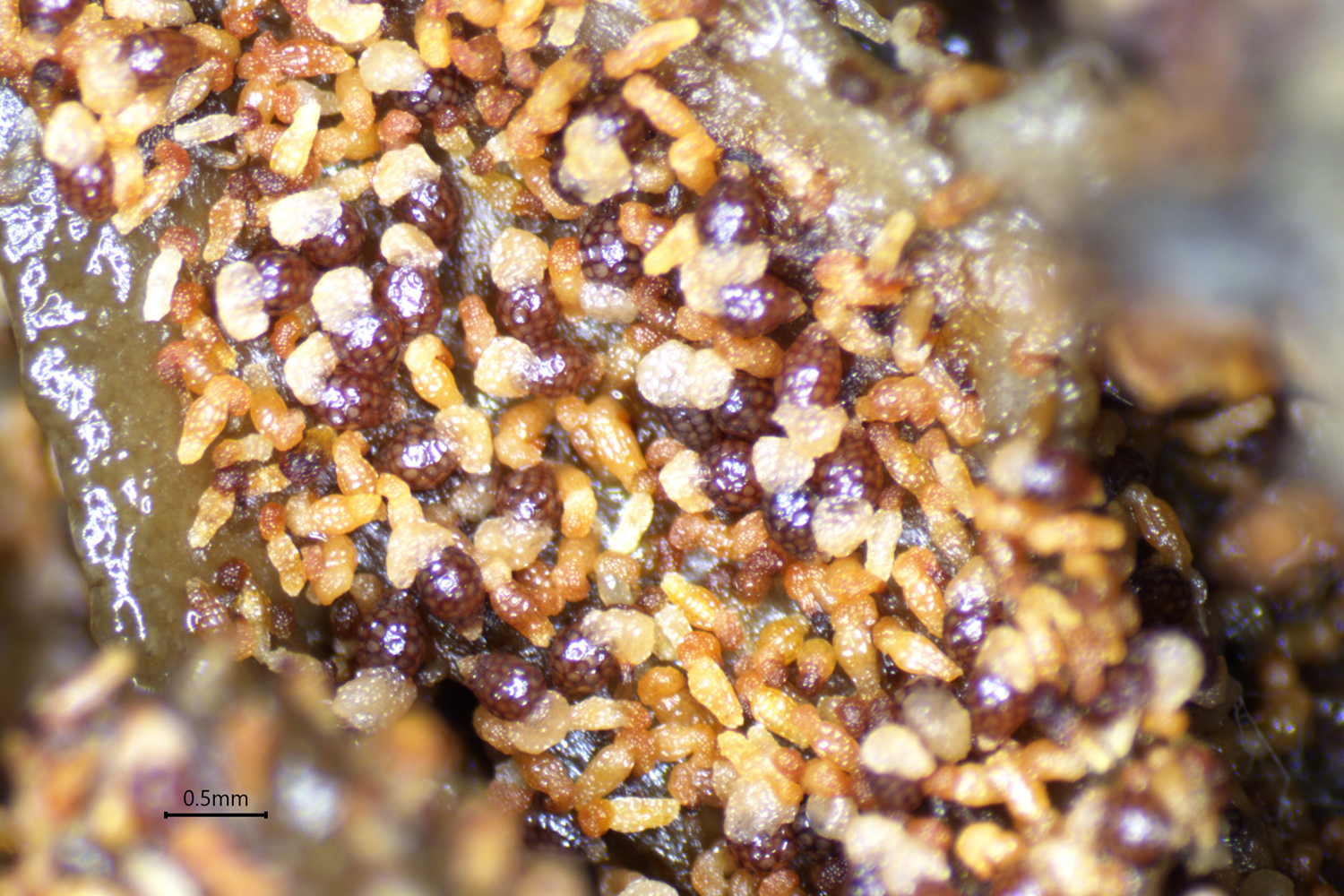

A fresh fruit looked under the microscope – brown: fertile, orange: sterile, and white are aril |

Could Rafflesciaceae plants have ever occurred in Hong Kong?

Potentially! As there is hard evidence of Dipterocarp trees once growing in Fujian, there is definitely the possibility that Rafflesiaceae once grew in this part of China, too. Biologically, Rafflesia is so specialised that the only visible part is the flower, with neither roots, leaves nor stem ever venturing outside their host. In addition, Rafflesiaceae flowers decompose rapidly once flowering has ended, and therefore they cannot be fossilised. Nevertheless, their host genus Tetrastigma is widespread and abundant in Hong Kong, and the warm, moist climate of Hong Kong is certainly apt for these plants. We know that many once-native plants have become extinct here, as a result of our ancestors’ efforts in clearing the original forests. We can only speculate as to what these forests once contained, but the flora of not-so-distant parts of tropical Asia give us strong clues.

A drone photo of Hong Kong forest

It's an incredible revelation to consider that relatives of the world’s largest flower may once have graced Hong Kong’s forests!